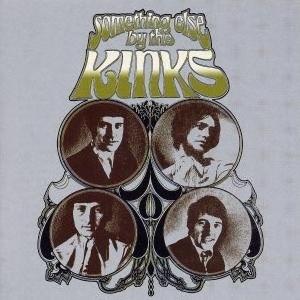

While released overseas on the closing cusp of the Summer of Love, the Kinks’ next album didn’t make it out in America until the first month of 1968.

Something Else By The Kinks is a terribly understated title for the band’s best work to date. In addition to even more excellent Ray Davies tunes, we can hear the emergence of Dave Davies as a songwriter, as it includes songs that had recently released as solo singles. But because

Something Else is another one of those finely sequenced albums, we’ll tackle them in this context.

While seemingly every other British band spent part of the era dabbling in psychedelia, the Kinks were decidedly set on simpler passions. “David Watts” might as well be a leftover from the mod era, describing a boy who, unlike the narrator, dresses right, looks right, and “is so gay and fancy-free”. Dave comes up strong with “Death Of A Clown”, a blatantly Dylanesque plaint, both in words and tone, but with ethereal “la-la-la” transitions that keep it from being too much of a ripoff. The balance between the brothers is explored with some maturity in “Two Sisters”, with a harpsichord framing the portrait of freewheeling single Sybilla and trapped housewife Priscilla. (Spoiler alert: there’s a happy ending.) The quiet samba of “No Return” provides musical variety, particularly before the Cockney smoker’s lament of “Harry Rag”. “Tin Soldier Man” could be seen as a protest song, considering the era, but this particular figure gets to go home to his wife and kids and “keep his uniform tidy”. “Situation Vacant” returns to the theme of modern people trying to get by in the day’s economy, but this time blaming the breakdown of the marriage on the nagging mother-in-law. (The guitar solos provide evidence that Keith Richard heard the album a few times.)

Dave kicks off side two with the randy “Love Me Till The Sun Shines”, a decent, sneaky rocker. “Lazy Old Sun” seems to go out of its way to be off-pitch, with horn parts, a slide bass, and incessant maracas managing to sonically illustrate the more unbearable days of summer. But what makes Ray happiest, of course, is “Afternoon Tea”, particularly with the one he loves. Meanwhile, Dave misses his “Funny Face”, from whom he’s separated by windows, gates, and doctors. “End Of The Season” begins with sound effects right off of Face To Face (indeed, the song was left over from those sessions) before turning to something of a cabaret spoof. Closing the set, though hardly tacked on, is “Waterloo Sunset”, the previous summer’s hit single. Several critics have called it one of the loveliest songs of the 20th century, and while first impressions may not support it, it truly is one of those songs that sticks with you, with simple changes and a melancholy narrator watching two kids named Terry and Julie crossing over to what he imagines must be a better future.

Dave’s contributions notwithstanding, Something Else By The Kinks captures the band as they escaped from under producer Shel Talmy’s thumb to the apparent preference of Ray’s, who gets co-credit for producing. And while he’s only briefly mentioned by his first name on the back cover, the more intricate piano parts are played by good old Nicky Hopkins, who certainly deserves credit for why the tracks sound as good as they do. (Once again, expanded editions released overseas are worth digging up, as they include many contemporary singles and B-sides just as good as the A-sides that made it to the album. And then there’s the exquisite “Little Women”, which only got as far as a backing track with Mellotron overdubs.)

The Kinks Something Else By The Kinks (1968)—4

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-5132629-1444147241-7784.jpeg.jpg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-5582498-1397192147-9989.jpeg.jpg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-4289790-1360829196-2909.jpeg.jpg)