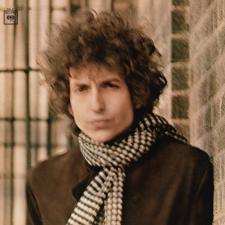

In love with Philly soul, Bowie’s next album was recorded rather quickly, and largely in the center of the action at Philadelphia’s Sigma Sound. David Sanborn came over from the tour, but the key addition to the band was guitarist Carlos Alomar, who would be the silent weapon on many Bowie albums and tours henceforth.

In love with Philly soul, Bowie’s next album was recorded rather quickly, and largely in the center of the action at Philadelphia’s Sigma Sound. David Sanborn came over from the tour, but the key addition to the band was guitarist Carlos Alomar, who would be the silent weapon on many Bowie albums and tours henceforth.Young Americans was a popular album, thanks to its breathless title track. The rest of the first side explores different soul styles of one word each: “Win” is smooth and silky; “Fascination” is fat and funky; and “Right” gets into the groove with a minimalist contrast to the patter utilized throughout.

That’s a good start, but side two is pretty schizophrenic. “Somebody Up There Likes Me” is another long one that tries but doesn’t always hold. His love of obscure covers is further demonstrated by “Across The Universe”, which John Lennon himself endorsed, but it doesn’t really go anywhere until the end once he switches the croon to a shout. “Can You Hear Me” slows things down to distraction, and “Fame” became another unlikely #1 hit. Lennon got credit for the riff, and the lyrics (when you can decipher them) are pretty pointed. The song takes the soul we’ve been hearing upside down, leaving a clue to his next stop.

Bowie was so excited by the two Lennon-oriented tracks that he bumped three originals from the album; all would appear as bonus tracks in the CD age. Two of them are lost Bowie classics; “Who Can I Be Now?” would have been a welcome highlight, and “It’s Gonna Be Me” is another effective torch song. (An alternate mix took its place this century.) However, the pointless disco retread “John I’m Only Dancing (Again) 1975” had originally sat in the can for a few years, came out on a single once he was two styles past the original recording, and took up space on the otherwise worthy Changestwobowie compilation. Those not familiar with the original would have been confused. But Bowie had certainly succeeded in confounding expectations more than once, and each time, no sooner had he found a hit style, he turned on it.

A previous version of this review rated the album half a star lower than it is now; maybe it’s nostalgia, or maybe it really isn’t as disappointing as we recalled. But for further perspective on Young Americans, 2016’s retrospective Who Can I Be Now? box set included the album alongside its original Lennon-free sequence, when it was known as The Gouster. This version begins with “John, I’m Only Dancing (Again)”, continuing side one with “Somebody Up There” and “It’s Gonna Be Me”; side two has “Who Can I Be Now?”, “Can You Hear Me”, “Young Americans” and “Right”. All of the songs that made the eventual album, save the title track, appear in earlier mixes. It doesn’t replace the album we’ve known all these years, but is informative.

David Bowie Young Americans (1975)—3

1991 Rykodisc: same as 1975, plus 3 extra tracks

2007 Collector’s Edition: same as 1991, plus DVD