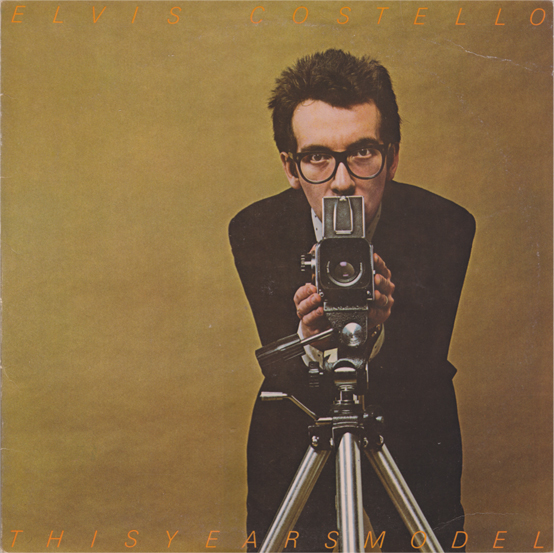

Armed Forces was successful, but a handful of PR mistakes collided to derail any momentum Elvis Costello had gained in America. With the exception of a few scattered singles, his career never really recovered on this side of the pond.

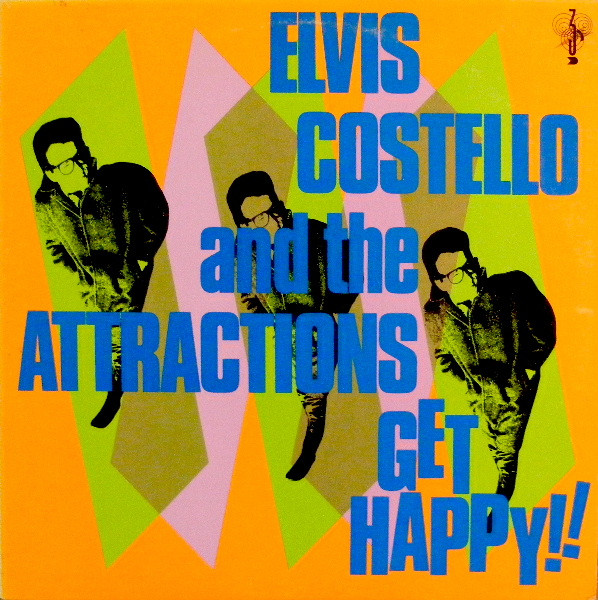

Armed Forces was successful, but a handful of PR mistakes collided to derail any momentum Elvis Costello had gained in America. With the exception of a few scattered singles, his career never really recovered on this side of the pond.Back home in the UK, he he produced the excellent first album by The Specials, then decamped to Holland with the Attractions to work on his next album. This time the influence was a stack of Motown and Stax 45s, with the ska and dub sounds of the Specials hanging over the edges. With ten songs crammed onto each side, Get Happy!! delivers a hell of a bang for your buck.

Despite the misleading back cover listing that swapped the sides, “Love For Tender” sets the pace with pointed puns and breakneck speed, followed by the contrast of the softer soul in “Opportunity”. Such give and take between styles continues throughout the side, with no noticeable repetition. Nearly every song has something to offer: “The Imposter” would give him a pseudonym down the road; “Secondary Modern” goes back to soft soul to complain with a few British expressions to confound Americans; “King Horse” is a showstopper with Pete Thomas clever using one part of his kit at a time for accents and Bruce Thomas all over his fretboard. “Possession” and the one-man-band “New Amsterdam” ape the Beatles without stealing, while “Men Called Uncle” (singular on the original LP, not plural) nods at pop art with its throwback title and tight structure. “Clowntime Is Over” is another showstopper of a performance, and “High Fidelity” takes his wordplay and vocal ability to even higher levels. And that’s just side one.

Side two is virtually bookended by a couple of obscure R&B covers: Sam & Dave’s “I Can’t Stand Up For Falling Down” is about twice as fast, while “I Stand Accused”—which Elvis probably heard by the Merseybeats—is also given an amphetamine kick. “Black And White World” crashes its way through to “5ive Gears In Reverse”, both showcases for Steve Nieve on the Hammond B-3, but Bruce inserts some very deft lines himself, and dominates the dub-tinged “B Movie”. “Motel Matches” works in a reference to Sam Cooke for a near-ballad, while “Human Touch” is near ska. “Beaten To The Punch” is a great trashy tune, complete with Stax-style guitar solo, just as “Temptation” directly quotes Booker T & the MG’s. And again, even though the cover said it ends side two, the true finale is the pointed, passionate “Riot Act”, the angry suicide note that closes the album.

While the original LP boasted twenty tracks, each of the reissues has trumpeted a similar abundance. The Ryko version was packed to capacity, adding ten B-sides and/or demos (most of which were familiar from Taking Liberties), plus an unlisted snippet of the demo for “Love For Tender”, which cut off abruptly. In a nod to the original back cover, the track list was printed in reverse order. The Rhino version included a whopping fifty tracks on two discs—the original LP on one, with the Ryko bonuses (including the complete “Love For Tender” demo) and additional outtakes, demos, and live tracks, pretty much grouped in that order, on the other. The new (to us) alternate takes are especially fascinating, as they provide a bizarro version of the album that’s more modern ska than classic soul, except in the case of “B Movie”, which is the opposite. There are even three songs that would eventually be redone for his next album; plus, the demo for “Seven O’Clock” has lyrics that would end up in another song there too. (Keep listening at the end of the disc for a clever radio ad.)

The extras give a glimpse at more of the influences that shaped the album, as well as some one-man-band tracks that kept collectors busy when they had been released on EPs or as B-sides. But even taken on its own, Get Happy!! is truly one of his best.

Elvis Costello & The Attractions Get Happy!! (1980)—5

1994 Rykodisc: same as 1980, plus 11 extra tracks

2003 Rhino: same as 1994, plus 19 extra tracks

:format(webp):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-2044230-1357423019-5347.jpeg.jpg)